I’m sitting in a cool breeze on the terrace café of Panama City’s fabulous Museum of Biodiversity, looking out to a seaful of ships waiting to enter the canal and feeding small pieces of empanada to a grackle. The museum, designed by Canadian Frank Gehry (of Guggenheim fame) is a riot of primary blue, red and yellow angled rooves like huge colourful leaves, clustered on concrete and steel trunks and branches and surrounded by water which you can see through the building’s infrastructure from almost all directions. It was biodiversity-inspired, recalling, according to the guide book (and depending on who you ask) ‘a forest canopy, a kaleidoscope of butterflies, a macaw’s wings or’ you guessed it, ‘a cargo ship full of containers.’

I’m sitting in a cool breeze on the terrace café of Panama City’s fabulous Museum of Biodiversity, looking out to a seaful of ships waiting to enter the canal and feeding small pieces of empanada to a grackle. The museum, designed by Canadian Frank Gehry (of Guggenheim fame) is a riot of primary blue, red and yellow angled rooves like huge colourful leaves, clustered on concrete and steel trunks and branches and surrounded by water which you can see through the building’s infrastructure from almost all directions. It was biodiversity-inspired, recalling, according to the guide book (and depending on who you ask) ‘a forest canopy, a kaleidoscope of butterflies, a macaw’s wings or’ you guessed it, ‘a cargo ship full of containers.’

The museum, a fusion of art and science, was designed, in the words of E.O.Wilson, ‘to support the study, understanding and loving preservation of biodiversity.’ Wilson himself, his voice magically conjured up in slightly distant English on the hand-held audio-device, defines biodiversity as ‘all the variation you find in living creatures around the world: from ecosystems to species to the genes that describe the traits of species’ – nested levels of biodiversity within the biosphere, that thin and fabulous layer of our planet and its atmosphere that supports all life.

The museum is stunning, inside and out. It’s information rich, packed with visually – and in some cases aurally – powerful displays about what biodiversity is, why it matters and what’s happening to it. Yet there is also a sort of relaxed peacefulness in being there, too. I read later that this was intentional: one of the main design goals was to move ‘away from the idea of a building containing collections, in favour of it being a provoker of thoughts. In a world where we are bombarded with a dizzying and incessant flow of information, the BioMuseo invites visitors to pause and find themselves again with the purest and most childlike curiosity….’

The why-biodiversity-matters bit is mostly expressed in terms of ecosystem services, minor things like soil fertility, clean air and water, CO2 absorption, rain creation, erosion and flood prevention, medical research and scientific knowledge, plus the so-called ‘soft’ services such as recreation, inspiration and delight. There are great examples of biodiversity-sourced usefulness, like the pain killers derived from a cone snail or the insights into nervous systems gained by studying the skin of poison dart frogs. And my favourite: innovation through biomimicry in the form of figuring out how geckos walk upside down. Not thanks to suction pads, apparently, but incredibly fine hairs that allow them to harness sub-atomic forces. Basically, geckos defy gravity by clinging on to atoms! The museum quotes that infamous figure of $30 trillion as an estimate of the annual – annual – worth of these ‘services’. And it also raises the all-important intrinsic value question (well, sort of raises it) by asking whether you can put a price on a cure for cancer or a beautiful, rare orchid.

The why-biodiversity-matters bit is mostly expressed in terms of ecosystem services, minor things like soil fertility, clean air and water, CO2 absorption, rain creation, erosion and flood prevention, medical research and scientific knowledge, plus the so-called ‘soft’ services such as recreation, inspiration and delight. There are great examples of biodiversity-sourced usefulness, like the pain killers derived from a cone snail or the insights into nervous systems gained by studying the skin of poison dart frogs. And my favourite: innovation through biomimicry in the form of figuring out how geckos walk upside down. Not thanks to suction pads, apparently, but incredibly fine hairs that allow them to harness sub-atomic forces. Basically, geckos defy gravity by clinging on to atoms! The museum quotes that infamous figure of $30 trillion as an estimate of the annual – annual – worth of these ‘services’. And it also raises the all-important intrinsic value question (well, sort of raises it) by asking whether you can put a price on a cure for cancer or a beautiful, rare orchid.

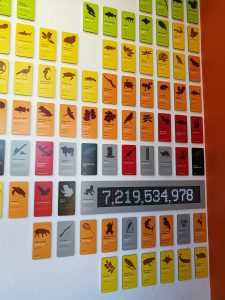

And the threats? Well, humans, of course and tragically, through habitat degradation, climate change, invasive  species and diseases, pollution, over-fishing and over-hunting, collection from the wild and so on. The over-arching headline in this section is our growing population. A flickering population counter graphically illustrates this relentless increase at a rate of about 2 additional humans per second. The hair-raising people-counter is surrounded by a series of panels illustrating the consequences for Panamanian species (amongst others), from extinct to unthreatened. Good news: the nine-banded armadillo, like the crazy character we saw in Corcovado, is in the latter category….

species and diseases, pollution, over-fishing and over-hunting, collection from the wild and so on. The over-arching headline in this section is our growing population. A flickering population counter graphically illustrates this relentless increase at a rate of about 2 additional humans per second. The hair-raising people-counter is surrounded by a series of panels illustrating the consequences for Panamanian species (amongst others), from extinct to unthreatened. Good news: the nine-banded armadillo, like the crazy character we saw in Corcovado, is in the latter category….

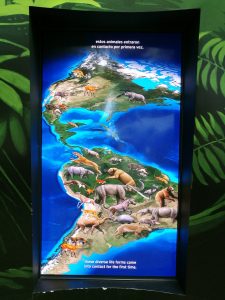

The exhibition’s main focus is the creation of the Panama land bridge. Panama is one of the most diverse countries on earth, with more species of trees, insects and birds in one (admittedly well-chosen) hectare than the whole of North America. One of the reasons for this extraordinary diversity is the geological event that lead to ‘the great biotic interchange.’ About 40 million years ago, shifts in tectonic plates and the dramatic, volcano-related consequences, eventually created a land bridge between Colombia and Panama. This in turn would allow hitherto separated species from North and South America to meet and merge.

The exhibition’s main focus is the creation of the Panama land bridge. Panama is one of the most diverse countries on earth, with more species of trees, insects and birds in one (admittedly well-chosen) hectare than the whole of North America. One of the reasons for this extraordinary diversity is the geological event that lead to ‘the great biotic interchange.’ About 40 million years ago, shifts in tectonic plates and the dramatic, volcano-related consequences, eventually created a land bridge between Colombia and Panama. This in turn would allow hitherto separated species from North and South America to meet and merge.

The main interchange happened about 3 million years ago, a time when many

The main interchange happened about 3 million years ago, a time when many  massive species of animals and birds still roamed each continent. A six foot high CGI offers a roaring impression of what might have happened when the north-bound giant sloths met the south bound sabre tooth cats. And, the centre-piece of the museum, a brilliant, dynamic sculpture depicting this extraordinary north/sound mingling, hordes of previously separated creatures crossing into a brave new world: horses and big cats from the north meeting marsupials, armadillos and mastodon from the south. Not a few of these are now extinct, of course – including the giant sloth and the condor like ‘thunder-bird’ (named for the noise of its pounding 6m wings) but many existing animals and birds across both continents have shared ancestors from ‘the great biotic interchange’.

massive species of animals and birds still roamed each continent. A six foot high CGI offers a roaring impression of what might have happened when the north-bound giant sloths met the south bound sabre tooth cats. And, the centre-piece of the museum, a brilliant, dynamic sculpture depicting this extraordinary north/sound mingling, hordes of previously separated creatures crossing into a brave new world: horses and big cats from the north meeting marsupials, armadillos and mastodon from the south. Not a few of these are now extinct, of course – including the giant sloth and the condor like ‘thunder-bird’ (named for the noise of its pounding 6m wings) but many existing animals and birds across both continents have shared ancestors from ‘the great biotic interchange’.

I know I’m biased, but I was captivated. Brilliantly presented, it’s hard to imagine not being excited and moved – not to mention informed – by these displays. But, suddenly evicted into a section on Panamanian cultural history, I fell to wondering whether the contribution to the ‘loving preservation’ of the biodiversity it so brilliantly depicts couldn’t go a few stages further. And why it doesn’t; especially given the huge amount of thought invested in the museum’s communication strategy.

This strategy includes the use of ‘devices of wonder’ with the aim of engaging the visitor ‘as a more active participant in the search for answers’ rather than simply as a passive recipient of information. Yet there is virtually nothing that tries to engage the visitor as an active participant in nature conservation, or even in nature. The display opens with the statement, ‘estamos contectados con cada ser viviente’ (we are all connected with everything that lives). And, in the cultural section, there is some discussion of the need for more to be done in relation to nature conservation, mainly focussing on protected areas; plus a brief discussion of low impact, pro-biodiversity farming. But couldn’t there be something about how biodiversity and nature conservation can and should actively involve all of us, not just scientists studying it, or nature conservation professionals working on it in protected areas? Where are the links between our ordinary lives and our impacts – good and bad – on biodiversity; or the presentation of nature as everywhere and ourselves as very much in it and part of it? It’s the ‘nature out there’ mindset again, plus the ‘nature protection is the job of professionals’ mindset ….

Andrea Ahumada shows me the femur bone of a giant sloth. The small bone is a human femur for comparison!

The giant sloth…