Rosamira had told me I would almost certainly see monkeys. Not just any old monkeys, either, but Cotton Top Tamarin monkeys, or Titis; tiny creatures with a messy white hairdo that are only found in NW Colombia. And so I detoured to the small town of Santa Catalina, about half a day from Cartagena, and spent a lovely evening at the house of another amazing woman working on environmental issues, Francy from Proyecto Titi.

Next morning we drove a short distance to one of Proyecto Titi’s reserves and walked into the forest. Me, Francy and Felix – who has been working with Cotton Tops for 30 years – crunching over dry leaves in the immense heat with the extraordinary sounds of Howler monkeys ricocheting around us. ‘The Howlers are big and noisy but very peaceful,’ Francy told me. ‘We’ve seen Howlers and Cotton Tops sharing the same tree.’

Next morning we drove a short distance to one of Proyecto Titi’s reserves and walked into the forest. Me, Francy and Felix – who has been working with Cotton Tops for 30 years – crunching over dry leaves in the immense heat with the extraordinary sounds of Howler monkeys ricocheting around us. ‘The Howlers are big and noisy but very peaceful,’ Francy told me. ‘We’ve seen Howlers and Cotton Tops sharing the same tree.’

Rosamira, Executive Director of Proyecto Titi, a winner of the prestigious Whitely Fund for Nature award, had been optimistic about my chances of meeting the monkeys because, as part of a long-term study of their behaviour and habitat and needs, this troupe have become accustomed to people. And sure enough, after a longish wait and just as I’d sadly resigned myself to their not turning up, Felix and Francy both pointed at once to the same tree. They are here, they are here!!

With the agility of squirrels, first one, then several small creatures swung down towards us. White mop of a mane swept back from a dark, skull-like face, white fur on their tummies and legs, long fingers and toes and grey-brown furry backs. ‘And that one,’ said Francy, pointing to the creature who appeared boldest, ‘is Tamara.’ According to the text-books, Cotton Tops live to around 6 or 7 years old in the wild. Tamara is known to be 16. What’s more, her partner of many years having died, (Titis are monogamous), Tamara had not long acquired a new husband, 13 years her junior.

Another thing that’s become clear from the research, other than don’t assume the textbooks have it right, is that these monkeys need very specific kinds of trees. These include, not just trees for food and as transport infrastructure – Titis never touch the ground – but trees for sleeping in, about which they are particularly choosy. They prefer tall ones, ideally with spikey trunks to deter intruders and definitely with numerous large branches, and good leaf cover. These trees are almost always at least a couple of decades old and, since they change sleeping trees every night for security reasons, the monkeys need a good supply of them. ‘They sleep altogether in a circle on one of the branches,’ said Francy, ‘shoulders touching, kids in the middle….’

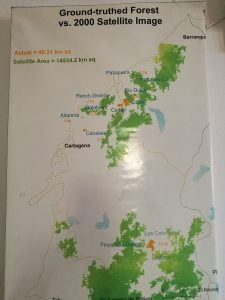

One of the reasons Titi monkeys are so endangered is not just lack of trees, but lack of the right kinds of trees. According to satellite data, only 5% of their habitat remains. Ground-truth this data against field observation and it reduces to 2%. 2%! ‘That’s why forest conservation and reforestation is absolutely critical,’ Felix (translated by Francy) explained. ‘And of course, protect the habitat for these monkeys and you protect it for many thousands of other species too.’

One of the reasons Titi monkeys are so endangered is not just lack of trees, but lack of the right kinds of trees. According to satellite data, only 5% of their habitat remains. Ground-truth this data against field observation and it reduces to 2%. 2%! ‘That’s why forest conservation and reforestation is absolutely critical,’ Felix (translated by Francy) explained. ‘And of course, protect the habitat for these monkeys and you protect it for many thousands of other species too.’

What I learned at Proyecto Titi confirmed a theme that’s emerging with super-clarity from all the projects so far. It’s stating the obvious I guess, but I’ve experienced it much more vividly here in Colombia than, say, England. You cannot separate conserving nature from tackling poverty.

Of course, we know that systemic poverty and environmental degradation have shared root causes in the particularly aggressive, compassion-free form of neo-liberal growth-based capitalism that is currently sweeping the world ….. But here in Colombia, the more immediate links are starkly evident too.

Gabriel had talked about it in Cartagena when he told me how local fishermen were exhausting their own fish stocks because they knew no other way to feed their families; and about ‘fishing for life’ a fish-farming and coastal ecology project his university was involved in by way of alternative. On the Cianaga road in the north, I had seen astonishing quantities of fish, draped symmetrically over wooden slats, heads one end, tails the other; hundreds of small stalls selling – or hoping to sell – these fish in the stinking heat on the road. I’d been amazed at the number of small boats with lines and nets crowding the estuary in their hundreds. This couldn’t possibly be a sustainable level of fishing. But what alternative did those people have? It was in this area that I’d cycled past some really appalling favelas, acres of mud-coloured shacks with no clean water, no sanitation, no rubbish collection. Che Guevara was outraged at the levels of poverty he witnessed when he travelled through South America by motorbike in 1951. How can this level of poverty still be allowed to exist, in this fast modernising country with its so-called ‘booming economy’?

The Titis are threatened by relentless loss of forest cover, one cause of which is people clearing land of trees so they can farm, or people taking down trees for firewood because they have no other source of fuel (deforestation is very often driven by big companies rather than locals of course.) And there is a thriving albeit illegal trade in catching and selling wildlife as pets; with cute little monkeys evidently popular. If the only way people can get food and fuel and other things they need is to trap and sell monkeys or to cut down trees or to keep on catching fish even as their catch gets smaller and smaller or to hunt for turtles and turtle eggs, then that is what they will do. And so, to be effective, nature conservation and any attempt to protect biodiversity and other species has to involve developing sustainable, nature-friendly ways of meeting people’s basic needs and reducing the crippling levels of poverty that still exist here.

The Titis are threatened by relentless loss of forest cover, one cause of which is people clearing land of trees so they can farm, or people taking down trees for firewood because they have no other source of fuel (deforestation is very often driven by big companies rather than locals of course.) And there is a thriving albeit illegal trade in catching and selling wildlife as pets; with cute little monkeys evidently popular. If the only way people can get food and fuel and other things they need is to trap and sell monkeys or to cut down trees or to keep on catching fish even as their catch gets smaller and smaller or to hunt for turtles and turtle eggs, then that is what they will do. And so, to be effective, nature conservation and any attempt to protect biodiversity and other species has to involve developing sustainable, nature-friendly ways of meeting people’s basic needs and reducing the crippling levels of poverty that still exist here.

It’s not surprising, then, that all the projects I’ve visited so far have community development as key

components of their work. For Proyecto Titi, this includes a particularly ingenious approach to developing alternative incomes. ‘We involve local communities in collecting waste plastic,’ Francy explained,’ and then we show them how to turn this plastic into a sort of twine, and from twine into high end fashion handbags. We’ve also developed a process for chopping waste plastic into tiny pieces and turning them into fence posts. Much more durable than wooden ones. And they sell for a good price. It’s a win/win – you take a problem like plastic waste and turn it into a solution to another problem….’

components of their work. For Proyecto Titi, this includes a particularly ingenious approach to developing alternative incomes. ‘We involve local communities in collecting waste plastic,’ Francy explained,’ and then we show them how to turn this plastic into a sort of twine, and from twine into high end fashion handbags. We’ve also developed a process for chopping waste plastic into tiny pieces and turning them into fence posts. Much more durable than wooden ones. And they sell for a good price. It’s a win/win – you take a problem like plastic waste and turn it into a solution to another problem….’

All this and more was confirmed when, several weeks later, I met Tinka Plese, aka ‘the Jane Goodall of sloths’. Tinka, a Croatian who had been living in Colombia for 30 years, works at the sharp end of the wildlife pet trade. ‘When the small, cute, clingy young sloth that someone bought at the roadside and took home becomes a large and pissed off adult, of course, they often get dumped. When I first arrived in Colombia, someone asked me to look after two of these dumped sloths. And I realised, no-one here really knows that much about them…’

Her organisation, Fundacion Aiunau, has developed a huge body of knowledge about sloth, anteaters and armadillo, all members of the super-order Xenarthra (‘strange joints’). Sloths are one of the species most affected by illegal traffic in Colombia, and an alarming percentage of captured individuals – more than 90% – die. Put this together with deforestation and fragmentation of their habitat, and it’s not surprising that they are endangered. Fundacion Aiunau also runs a high-profile nation-wide anti-wildlife trade campaign, works on community engagement, education and development, (these multiple strands are also a recurring theme), and takes in creatures with a view to rehabilitating them and releasing them back into the wild.

‘We work on the principle of “compassionate conservation,’’’ Tinka explained, ‘bringing conservation biology and animal welfare together.’ In other words, every individual animal counts, not just the species as a whole. ‘We have two giant anteaters here at the moment, seriously injured when their forest was burned down. And a three-month old who we are beginning to teach how to be independent.’ The juvenile anteater was probably the most outrageously cute creature I have ever seen. Even at a distance – he is being prepared for release and so I wasn’t allowed to get too close or to handle him – I was smitten. No wonder people fall for them as pets. But with such awful consequences. ‘Basic supply and demand, said Tinka. ‘If you buy one of these creatures, you are creating demand. And more will be extracted, usually brutally, from the wild.’

It’s depressing stuff. But how good to know that people like Francy and Tinka and Rosamira and their colleagues are out there doing this kind of work. The more time I spend here, the more of them I find. And the more I am experiencing Colombia as a country of huge contrasts, from immense warmth and friendliness and generosity, diversity and beauty and brilliant environmental projects on the one hand; to the ongoing decimation of forests and other ecosystems, rich/poor money and power chasms, and the still-present undertone of violence.

If you would like to support the work of Proyecto Titi with a donation, you can do so here: http://www.proyectotiti.com/en-us/Donate

If you would like to support the work of Fundacion Aiunau

please click here: http://www.aiunau.org/en/#search-2