‘With a shared ethic of respect for the planet, we can create common solutions and lead by example in showing how to coexist with nature.’

César A. Franco Laverde, Director, Serraniagua Corporation

I arrived at the tiny mountain town of El Cairo via La Carbonera; a steady climb away from traffic and into birdsong and spectacular views, a military checkpoint and a night in an utterly eccentric once rather raunchy, now dilapidated full-of-former-glory hotel. My room had a vast en suite bathroom all done out in black and red, complete with jacuzzi. But nothing actually worked, bar one cold dribble of a shower on the floor below and a single lightbulb (by good fortune in my bathroom.) There was a

I arrived at the tiny mountain town of El Cairo via La Carbonera; a steady climb away from traffic and into birdsong and spectacular views, a military checkpoint and a night in an utterly eccentric once rather raunchy, now dilapidated full-of-former-glory hotel. My room had a vast en suite bathroom all done out in black and red, complete with jacuzzi. But nothing actually worked, bar one cold dribble of a shower on the floor below and a single lightbulb (by good fortune in my bathroom.) There was a  fabulous mountain view from the creaking balcony, though, and something eerily romantic about being the only guest and coming in and out at night with a headtorch.

fabulous mountain view from the creaking balcony, though, and something eerily romantic about being the only guest and coming in and out at night with a headtorch.

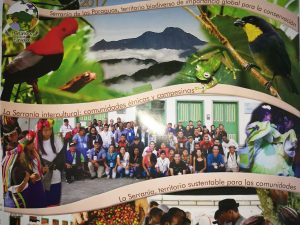

I was in El Cairo to find out about a project called Serraniagua. It’s a brilliant project, on many levels. In an area of high Andean forests with a staggering wealth of biodiversity and species endemism, on one level it’s all about traditional nature conservation, corridors, reserves, forest protection and regeneration. But, as with most of the projects I’ve visited so far, it’s also about community development and engagement; in this case working with local farmers to strengthen and take pride in traditional

I was in El Cairo to find out about a project called Serraniagua. It’s a brilliant project, on many levels. In an area of high Andean forests with a staggering wealth of biodiversity and species endemism, on one level it’s all about traditional nature conservation, corridors, reserves, forest protection and regeneration. But, as with most of the projects I’ve visited so far, it’s also about community development and engagement; in this case working with local farmers to strengthen and take pride in traditional  practices that are compatible with biodiversity, like low-impact, organic coffee-growing. (El Cairo is worth visiting for the coffee in the wonderful community café alone.) Serraniagua, a winner of the prestigious Equator Prize, goes further though, in two ways I hadn’t yet encountered. First, there is an emphasis on capacity building, so that local communities are not just engaged with nature conservation but actively informing and shaping its goals and the strategies for achieving them. Second, and this was particularly impactful for me, there is a strong focus on values.

practices that are compatible with biodiversity, like low-impact, organic coffee-growing. (El Cairo is worth visiting for the coffee in the wonderful community café alone.) Serraniagua, a winner of the prestigious Equator Prize, goes further though, in two ways I hadn’t yet encountered. First, there is an emphasis on capacity building, so that local communities are not just engaged with nature conservation but actively informing and shaping its goals and the strategies for achieving them. Second, and this was particularly impactful for me, there is a strong focus on values.

It’s a question I’ve lived with for years. Values. How do we change them? It’s blindingly clear that part of tackling our multiple environmental challenges must be values-transformation. We have to dispatch the me-me-me, it’s all about me individualism; and the overwhelming priority given to the value of stuff and money which, we are told, we must have to lead a happy life (an impoverished and utterly unsustainable version of what it takes for people to live well); and the correlating obsession with (equally unsustainable) indefinite economic growth as the indicator of social progress. But what do we replace these values with, and how do we do it?

Serraniagua offered one possible answer. It emerged via various conversations with Cesar, the brilliant, gentle and apparently ego-free founder/director. ‘If you want to preserve nature,’ Cesar said, on the front porch of his beautiful farm, ‘you have to change the cultures that are destroying nature.’ And instead? ‘Work with traditional cultures based on the values of respect, gratitude, spirituality, appreciation, friendship, community. People, animals, nature, delicious food, coffee, all can all co-exist. Interconnection is key. And balance: inside/outside, people/nature, what is sufficient for happiness/versus what is not enough. Work with these cultures to

Serraniagua offered one possible answer. It emerged via various conversations with Cesar, the brilliant, gentle and apparently ego-free founder/director. ‘If you want to preserve nature,’ Cesar said, on the front porch of his beautiful farm, ‘you have to change the cultures that are destroying nature.’ And instead? ‘Work with traditional cultures based on the values of respect, gratitude, spirituality, appreciation, friendship, community. People, animals, nature, delicious food, coffee, all can all co-exist. Interconnection is key. And balance: inside/outside, people/nature, what is sufficient for happiness/versus what is not enough. Work with these cultures to  strengthen these values, where they already exist or used to exist.’ For Cesar and Serraniagua, the focus is traditional farming communities; but it’s an approach that could be used in relation to any community that has, or used to have, or has the potential to have pro-nature, pro-human community, otherversionsofagoodlife values. Find those communities, and then figure out ways to establish, re-establish, strengthen, develop, re-vitalise and recharge those values there, in context; where they have roots and a good chance of growing stronger – and of crowding out the values of high-consumption materialism that are so hugely damaging to nature and human communities alike.

strengthen these values, where they already exist or used to exist.’ For Cesar and Serraniagua, the focus is traditional farming communities; but it’s an approach that could be used in relation to any community that has, or used to have, or has the potential to have pro-nature, pro-human community, otherversionsofagoodlife values. Find those communities, and then figure out ways to establish, re-establish, strengthen, develop, re-vitalise and recharge those values there, in context; where they have roots and a good chance of growing stronger – and of crowding out the values of high-consumption materialism that are so hugely damaging to nature and human communities alike.

For me, with a background in philosophy (often very abstract and not always  an aid to clear thinking!) it was a highly invigorating encounter with a very un-abstract approach to values and values change; manifested in relation to the people in the area where Serraniagua has been working for 20 years. During this time, people’s focus has shifted from their own individual profit to the health of the community and pride in what they’ve achieved together. And in terms of agricultural practice, Cesar’s own farm, for example, demonstrated these ‘alternative’ values in very real, practical ways.

an aid to clear thinking!) it was a highly invigorating encounter with a very un-abstract approach to values and values change; manifested in relation to the people in the area where Serraniagua has been working for 20 years. During this time, people’s focus has shifted from their own individual profit to the health of the community and pride in what they’ve achieved together. And in terms of agricultural practice, Cesar’s own farm, for example, demonstrated these ‘alternative’ values in very real, practical ways.

‘If you plant a coffee tree every square metre (or thereabouts) you get more coffee and more money,’ he said, looking out over the beautiful mix of trees just beyond the lovely old farmhouse. ‘But what about what you lose? You need to use chemicals to control the pests. You lose your water. You lose your soil and your biodiversity. You only have coffee

‘If you plant a coffee tree every square metre (or thereabouts) you get more coffee and more money,’ he said, looking out over the beautiful mix of trees just beyond the lovely old farmhouse. ‘But what about what you lose? You need to use chemicals to control the pests. You lose your water. You lose your soil and your biodiversity. You only have coffee  so you lose a generous farm with fruits and avocados etc. If you add up all those things that you lose….. this is where ‘shade’ coffee comes in. If instead you plant the coffee amongst plantains and avocados and other trees, they shade the coffee trees. The coffee matures more slowly and tastes better. You don’t need pesticides and you can produce organically. You keep soil and water and biodiversity. And you have a generous farm with much to offer guests…’ On Cesar’s farm, there was coffee grown in a mix with plantain, avocados, oranges and a bit of cacao, amongst other things. It was indeed a wonderful place to be a human guest. And, beyond the area that produced food for people, there was a forested, wilder area where a multitude of other species could and did live alongside people and farming.

so you lose a generous farm with fruits and avocados etc. If you add up all those things that you lose….. this is where ‘shade’ coffee comes in. If instead you plant the coffee amongst plantains and avocados and other trees, they shade the coffee trees. The coffee matures more slowly and tastes better. You don’t need pesticides and you can produce organically. You keep soil and water and biodiversity. And you have a generous farm with much to offer guests…’ On Cesar’s farm, there was coffee grown in a mix with plantain, avocados, oranges and a bit of cacao, amongst other things. It was indeed a wonderful place to be a human guest. And, beyond the area that produced food for people, there was a forested, wilder area where a multitude of other species could and did live alongside people and farming.

El Cairo and Serraniagua was my absolute favourite visit so far. I loved the mountain village and the people I met there, and I loved the project. I loved the  way the values of community/family/friendship/biodiversity/nature/flavour/coffee/good food/sociability appeared everywhere we went, and how very clearly it demonstrated that there are other ways of living a happy, high quality, sustainable life; ways that involve having some possessions and money for

way the values of community/family/friendship/biodiversity/nature/flavour/coffee/good food/sociability appeared everywhere we went, and how very clearly it demonstrated that there are other ways of living a happy, high quality, sustainable life; ways that involve having some possessions and money for  sure, but not vast and endlessly growing amounts. Ways in which relationships with human and nature communities are much more important than things and financial wealth. There were challenges too, of course, and I don’t want to sentimentalise or over-sweeten. But it seemed to me to have some real answers and to offer real hope. And, on a personal level, I felt at home there, the whole place summoning up memories of much-loved and influential early childhood visits to my Aunt Susan’s small-holding in the Welsh borders. I could happily have stayed a whole lot longer. Definitely my place in Colombia.

sure, but not vast and endlessly growing amounts. Ways in which relationships with human and nature communities are much more important than things and financial wealth. There were challenges too, of course, and I don’t want to sentimentalise or over-sweeten. But it seemed to me to have some real answers and to offer real hope. And, on a personal level, I felt at home there, the whole place summoning up memories of much-loved and influential early childhood visits to my Aunt Susan’s small-holding in the Welsh borders. I could happily have stayed a whole lot longer. Definitely my place in Colombia.

I left in great company, some local cyclists riding with me back up to La Carbonera. And then I rode on alone, mulling on the visit and how much it had turned out to mean. It was to prove to be a brilliant foil for the next visit, too; equally impactful, equally about values, though in a very different and very much darker way.