‘No to mining, yes to water and life.’

Cajamarca campaign slogan

I think Jennifer Rodriguez may be the bravest person I’ve ever met. 26 years old, with a young daughter, Jennifer was – and is – at the heart of the campaign to protect the small Colombian community of Cajamarca from the almost unbelievably destructive impacts of large-scale gold-mining. It’s a true David and Goliath tale with far-reaching implications. And it’s one that brings questions of values and power, of what really matters in life and who gets to decide, vividly into focus again; though in a very different and decidedly darker way from the lovely Serraniagua story. (See previous blog)

I think Jennifer Rodriguez may be the bravest person I’ve ever met. 26 years old, with a young daughter, Jennifer was – and is – at the heart of the campaign to protect the small Colombian community of Cajamarca from the almost unbelievably destructive impacts of large-scale gold-mining. It’s a true David and Goliath tale with far-reaching implications. And it’s one that brings questions of values and power, of what really matters in life and who gets to decide, vividly into focus again; though in a very different and decidedly darker way from the lovely Serraniagua story. (See previous blog)

I’d gone to Cajamarca in a car. I have a self-created rule that dictates I should  travel every inch of the north–south route from Cartagena to Cape Horn by bike if humanly possible; but that detours east, west (or indeed back north) by other means are allowed. Given that the (easterly) road between Armenia to Cajamarca includes a monstrous climb, has no hard shoulder, is utterly truck-infested and, on that day, was slick and at times downright riverlike with torrential rain, this was a decision that still makes me grin with relief when I think about it. Even better, the car belonged to a man called Alejandro, who I’d found thanks to extensive lead-following phone calls made by an Armenian environmental activist, who I’d met thanks to a Cali environmental activist…. Alejandro was great company, spoke excellent English and translated good-humouredly all day.

travel every inch of the north–south route from Cartagena to Cape Horn by bike if humanly possible; but that detours east, west (or indeed back north) by other means are allowed. Given that the (easterly) road between Armenia to Cajamarca includes a monstrous climb, has no hard shoulder, is utterly truck-infested and, on that day, was slick and at times downright riverlike with torrential rain, this was a decision that still makes me grin with relief when I think about it. Even better, the car belonged to a man called Alejandro, who I’d found thanks to extensive lead-following phone calls made by an Armenian environmental activist, who I’d met thanks to a Cali environmental activist…. Alejandro was great company, spoke excellent English and translated good-humouredly all day.

Cajamarca hit the press on March 27th, 2017, the day after a near unanimous  ‘No’ vote in a ‘consulta popular’ or public referendum against the development of a huge gold-mine. The mining company involved, AngloGold Ashanti, is the world’s third largest gold producer, and the project, dubbed ‘La Colosa’ because of its size, was backed by the Colombian government. Against them, a handful of activists, average age then around 21, who’d spent years carefully countering the ‘there are no risks’ propaganda from the mining company, educating the town and the outlying villages about the true implications of having La Colosa in their backyard, strengthening the community, and founding Cosajuca, a collective of young people focussed on social justice and the environment.

‘No’ vote in a ‘consulta popular’ or public referendum against the development of a huge gold-mine. The mining company involved, AngloGold Ashanti, is the world’s third largest gold producer, and the project, dubbed ‘La Colosa’ because of its size, was backed by the Colombian government. Against them, a handful of activists, average age then around 21, who’d spent years carefully countering the ‘there are no risks’ propaganda from the mining company, educating the town and the outlying villages about the true implications of having La Colosa in their backyard, strengthening the community, and founding Cosajuca, a collective of young people focussed on social justice and the environment.

‘The young people watched the older people here thinking they couldn’t do anything,’ Jennifer said. ‘But the young people didn’t feel like that. They believed they could save the town.’

‘The young people watched the older people here thinking they couldn’t do anything,’ Jennifer said. ‘But the young people didn’t feel like that. They believed they could save the town.’

We were sitting outside under a red umbrella at a table with an orange checked tablecloth, and talking in between pauses when the roaring and blasting and grinding of passing trucks made it impossible to hear, rather than just difficult. Jennifer had suggested ‘somewhere they do organic coffee’, which turned out to be a stand on one side of the main square; the side that’s also the main road to Bogota.

‘I was born in Bogota,’ Jennifer said, ‘but my mum came to Cajamarca with me 18 years ago, when I was 8. She fell in love with the town. Many young people here now feel the same. It’s quiet [in a non-truck-related sense] and safe and beautiful,’ she said, gesturing to the surrounding mountains. ‘Many young people go away of course, but a lot come back again. It’s a really good place for farming, with rich, fertile soil. We grow potatoes, arracacha, beans…’

And if the mine came here? Farming would be one of the main casualties, via soil pollution, contaminating crops. At the proposed La Colosa site, there’s about 0.82 grams of gold per ton of rocks; which would involve blasting about 1257 million tons of rock – a figure that gives some sense of how vast the waste would be. When previously underground layers of rock containing sulphides come into contact with air and water, the

And if the mine came here? Farming would be one of the main casualties, via soil pollution, contaminating crops. At the proposed La Colosa site, there’s about 0.82 grams of gold per ton of rocks; which would involve blasting about 1257 million tons of rock – a figure that gives some sense of how vast the waste would be. When previously underground layers of rock containing sulphides come into contact with air and water, the  resulting process of acidification can end up dissolving extremely harmful metals and metalloids, such as arsenic, into the soil; a process that carries on for many hundreds if not thousands of years after the mining is finished and is basically, in lawyer Polly Higgins’ language, an ecocide.

resulting process of acidification can end up dissolving extremely harmful metals and metalloids, such as arsenic, into the soil; a process that carries on for many hundreds if not thousands of years after the mining is finished and is basically, in lawyer Polly Higgins’ language, an ecocide.

Water of course, would be the other main casualty. Mercury is used to extract the gold from the rocks, and the potential for pollution from the tailings ponds, which here would be built at almost 10,000 feet above a major watershed, is mind-boggling. And not only that: water would also be needed in vast amounts for the gold-extraction process, diverting it from other more vital uses. (1g of gold needs 1,060 litres of water, making gold even more expensive in water than beef.)

And the end result? A substance whose main use is decorative. And even then, most of it is not even in circulation. According to Joan Martinez-Allier, lead author of the Environmental Justice Atlas, ‘[t]he Gold Global Council recently confirmed that only 7% of the gold extracted is used for electronic devices and tooth implants. Less than a tenth of it has industrial value and could be replaced by other alloys. 45% of the extraction is kept in vaults as treasures in the form of ingots and coins, and the remaining 47% is used to make jewellery….’ And much of that unworn and locked up. As Martinez-Allier goes on to say, ‘We are missing the point, the real valuables are water, soil and air, healthy ecosystems that sustain healthy people. Is it really worth to take the guts out of the Earth …. for a golden ring?’

Gold versus water and life. When you put it like that, the values-priority is blindingly clear. And yet, the power of companies like AngloGold Ashanti, who have their own armies and turnovers bigger than the GDP’s of entire countries, means that the extraction of gold gets prioritised over water and, indeed, life. One of the things I love about cycling is how fast it reconnects you with the saner version of this values-prioritisation; how it disconnects you from the value of glittering stuff and makes vivid the value of the basics. Food, water, shade, warmth, somewhere safe to sleep. Not cycling. These utterly ordinary things, so readily taken for granted, become total treasures. It must be one of the all-time ironies of life how simple a recipe for happiness just appreciating these things is; and how hard it is to stay in touch with that appreciation, in so-called ‘normal’ existence.

Gold versus water and life. When you put it like that, the values-priority is blindingly clear. And yet, the power of companies like AngloGold Ashanti, who have their own armies and turnovers bigger than the GDP’s of entire countries, means that the extraction of gold gets prioritised over water and, indeed, life. One of the things I love about cycling is how fast it reconnects you with the saner version of this values-prioritisation; how it disconnects you from the value of glittering stuff and makes vivid the value of the basics. Food, water, shade, warmth, somewhere safe to sleep. Not cycling. These utterly ordinary things, so readily taken for granted, become total treasures. It must be one of the all-time ironies of life how simple a recipe for happiness just appreciating these things is; and how hard it is to stay in touch with that appreciation, in so-called ‘normal’ existence.

———–

When I met Jennifer, a few weeks after the referendum, AGA had said they were determined to continue with the Colosa mine, despite that the result of the referendum is legally binding in Colombian law. Everyone was holding their breath, waiting to see what they – and the Colombian government – would do next.

‘We will do everything we possibly can within the law,’ Jennifer said. But if it comes to it, we will fight.’ The young people of Cajamarca, against a South African based company with its own army, accused of contaminating land and poisoning people in Ghana, and of financing paramilitary groups in the Democratic Republic of Congo? Operating in a country that according to Global Witness, is the third most dangerous in the world to be an environmentalist, with mining being the most deadly industry to protest against? This would not end well.

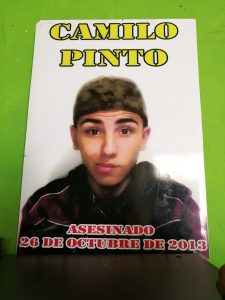

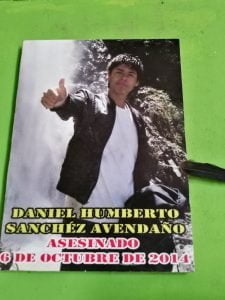

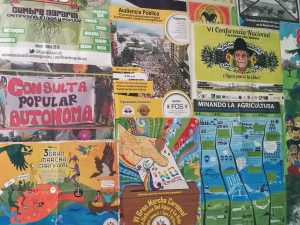

And it’s already been deadly for at least two young people. After coffee, we went to the Cosajuco office, walking past a cheerful line of yellow, green and blue ‘Willys Jeeps’, a sort of mountainous region taxi-service, through almost empty streets to a small green-painted building on a corner – none of it feeling remotely like the centre of a revolution. Inside, colourful campaign posters on the green walls, and a computer on a desk. And two large photographs of young men, Camilo Pinto and Daniel Humbertos Sanchez Avendano, who were

And it’s already been deadly for at least two young people. After coffee, we went to the Cosajuco office, walking past a cheerful line of yellow, green and blue ‘Willys Jeeps’, a sort of mountainous region taxi-service, through almost empty streets to a small green-painted building on a corner – none of it feeling remotely like the centre of a revolution. Inside, colourful campaign posters on the green walls, and a computer on a desk. And two large photographs of young men, Camilo Pinto and Daniel Humbertos Sanchez Avendano, who were  both involved in the campaign, and who both died under highly suspicious circumstances in 2013 and 2014. The photographs were worded unambiguously. ‘Asesinado’. One of the lads was found hanging from a tree, pronounced by the police to be suicide, though no-one locally believes it was. The other was shot in the stomach at a party, allegedly something to do with marijuana. It leaves you deeply chilled, and shifts the world on its axis more than a little, to learn about these kinds of consequences, visited on youngsters standing up for their community and lands.

both involved in the campaign, and who both died under highly suspicious circumstances in 2013 and 2014. The photographs were worded unambiguously. ‘Asesinado’. One of the lads was found hanging from a tree, pronounced by the police to be suicide, though no-one locally believes it was. The other was shot in the stomach at a party, allegedly something to do with marijuana. It leaves you deeply chilled, and shifts the world on its axis more than a little, to learn about these kinds of consequences, visited on youngsters standing up for their community and lands.

And here is Jennifer, carrying on with the work. I will never have that kind of bravery, and I hope Jennifer and the others don’t need it for ‘a fight’. With luck they won’t – since I visited, AGA has announced it is not going ahead with La Colosa. Truly tremendous news, and thanks in part to the attention focussed on Cajamarca nationally and internationally.

‘And that’s the point,’ Jennifer had said. ‘This isn’t just a local issue. The Cajamarca area provides food and water to great chunks of Colombia, including Bogota. And new ‘consulta populars’ can be helped by this one. It sets a brilliant precedent. There are already six or seven underway in Colombia, all to do with the extractive industries, gold, oil, gas-fracking. And the issue of corporate power, how it can so readily persuade supposedly democratic governments to make outrageously bad decisions, that’s an issue wherever there are corporations. The corporations take, trash and leave, decimating livelihoods, environments, communities. Everywhere. That’s one of the messages Cosajuca would like to send to the world.’

‘And that’s the point,’ Jennifer had said. ‘This isn’t just a local issue. The Cajamarca area provides food and water to great chunks of Colombia, including Bogota. And new ‘consulta populars’ can be helped by this one. It sets a brilliant precedent. There are already six or seven underway in Colombia, all to do with the extractive industries, gold, oil, gas-fracking. And the issue of corporate power, how it can so readily persuade supposedly democratic governments to make outrageously bad decisions, that’s an issue wherever there are corporations. The corporations take, trash and leave, decimating livelihoods, environments, communities. Everywhere. That’s one of the messages Cosajuca would like to send to the world.’

And the other? ‘Perseverance and hope. And the importance of being united. The big companies are big monsters. They don’t care what they damage and destroy in the process of taking what they want. But a united town or community can stand up against them….’

Alejandro and I drove back to Armenia, in silence for the first hour or so, moved and, yes, shocked by what we’d learned and heard. I’d come to South America to ride my bike in big mountains and explore biodiversity – its value, what’s damaging it, what can be done to protect it. I suppose I’d mostly imagined myself hanging out in nature reserves, feasting my eyes on amazing animals and plants. To an extent it has been like that, of course. What I hadn’t anticipated was grappling, albeit from my privileged and safe distance, with the dark and glittering and dangerous world of mining; with the immense costs on life and land and people of the quest for the vast monetary wealth that comes – to a few – from extracting gold (not to mention copper, oil and gas) from the earth.

Nor had I anticipated the impact of, as at the same time as colliding head-on with these black stories, meeting individuals for whom ‘inspiring’ seems a wishy-washy, inadequate word. Individuals who vividly demonstrate what an astonishing amount can be achieved by a handful of smart folk with passion and vision and energy and commitment. With perseverance and hope. I suppose the juxtaposition is not really surprising: the one invokes the other. But it can still take your breath away, even more effectively than cycling at altitude.

‘